Have We Demystified Critical Thinking?

Psychology faculty agree that critical thinking instruction is important (Appleby, 2006; Halpern, 2002), but they cannot agree on a precise definition of critical thinking. Critical thinking is a “mystified concept” (Minnich, 1990, p. 51), a problem that Halonen (1995) addressed over a decade ago.

In this chapter, we attempt to further demystify the concept of critical thinking. We begin by looking at student and faculty perceptions of critical thinking. Building on the work of Halonen (1995) and Halpern (2002, 2003), we then describe specific activities and techniques designed to address the propensity, cognitive, and metacognitive components of critical thinking.

Student and Faculty Views of Critical Thinking

Twenty psychology faculty and 170 undergraduate psychology majors completed an online survey regarding critical thinking and how it is addressed in the classroom. In addition to open-ended questions, we included a forced-choice question, where respondents chose the best among four different definitions of critical thinking.

Students and faculty agreed that the best definition was that provided by Halonen. the propensity and skills to engage in activity with reflective skepticism focused on deciding what to believe or do. Most students and faculty also agreed that critical thinking was important in facilitating learning. Not surprisingly, freshmen rated critical thinking as less important than other participants did. More advanced students and those who had taken a research methods course were more likely to appreciate the importance of critical thinking

Critical Thinking Framework

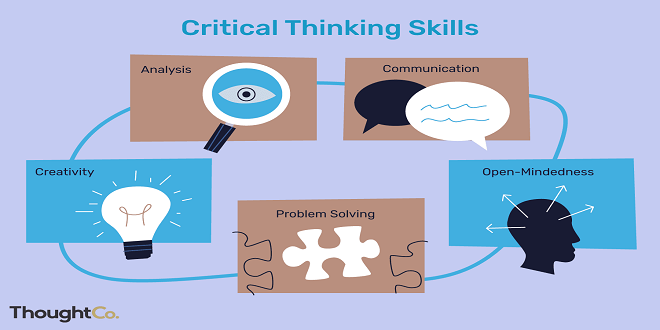

Halonen (1995) urged faculty to focus on critical thinking skills and proposed a framework to help “demystify” critical thinking. We used Halonen’s framework to help identify best practices for fostering critical thinking (see Figure 3.1). The framework includes both the cognitive and propensity elements of critical thinking. Halpern (2002, 2003) presented a similar model for teaching critical thinking skills. Halpern recommended learning activities that

Propensity Components

Students who have the skills to think critically do not always use those skills. Like all thinkers, students are “cognitive misers (Taylor, 1981) who have neither the ability nor the motivation to think critically about every issue. Critical thinking takes effort, and students will exert that effort only when they are sufficiently motivated to do so. What propensity elements motivate students to think critically? Furthermore, how can we as instructors nurture the propensity to think critically?

Before our students can think critically, they need to recognize the attitudes or dispositions of a critical thinker. It is not enough for us to tell them: “Think critically!” We must define the concept for them and provide specific guidelines for how to do critical thinking.

Wade and Tavris (2002) stated that critical thinkers should (a) ask questions and be willing to wonder, (b) define problems clearly, (c) examine evidence, (d) analyze assumptions and biases, (e) avoid emotional reasoning, (f) avoid oversimplification, (g) consider alternative interpretations, and (h) tolerate uncertainty. These guidelines help to demystify the concept of critical thinking for students.